It was the first Civil War monument in Wisconsin, erected in 1868, three years after the end of the war. A few months ago, I decided that while I was living in Wisconsin, I should try to visit as many local monuments as possible, especially the earliest ones, as one of my aims in the first chapter of my dissertation is to think about the origins of the soldier monument.

I know this doesn't look like a very exciting monument. Essentially a granite block, it could be a marker for pretty much anything: a grave, a boundary, a nearly-forgotten minor skirmish. What excites me, however, is the strangeness of its particulars.

Let's take a quick look at the site:

This is really strange. Most of the monuments I visit are located in the middle of bustling towns, usually next to a library, courthouse, school, church, or other official building. While they are not always venerated on a daily basis, they are at least highly visible, with lots of foot and vehicle traffic going past. This particular monument is close to the town hall, yes, but the location is completely rural, a copse of somber evergreen trees surrounded by (in late April) snowy fields. From my explorations so far, I think the community of Rhine is more a collection of homesteads, so this monument may serve as a town center of sorts, although in a much different way than I have experienced before.

The inscriptions are also pretty worthwhile. On the south side is the verse, "You wish to know the valor of the West; go ask the rebels for they know it best." One of the suggestions I received over and over again when I first started to frame this project was that my thinking at first focused too narrowly on the binary of North and South, when really, during the Civ

il War, our nation had three distinct regions: North, South, and West. This inscription suggests to me that there's a lot more to mid-century Western regional identity than I've been allowing myself to consider.

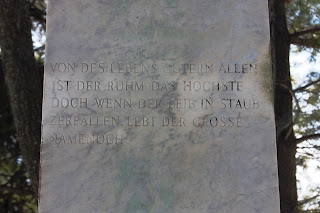

il War, our nation had three distinct regions: North, South, and West. This inscription suggests to me that there's a lot more to mid-century Western regional identity than I've been allowing myself to consider.And on the north face of the monument is an inscription in German; the German text is illustrated in this photo, and it translates as: "Of all the good things in life, / Honor is the greatest one. / Though the body goes to dust, / A great name lives on!" I kind of love this. For one thing, it reflects that the town of Rhine (naturally) had a strong German-American identity. Even more importantly, since the German text is not the translation of the English text on the opposite side, and since it is not translated into English anywhere on the monument, this shaft of granite assumes that its viewers will have pretty specialized bilingual knowledge. Pretty cool for a monument that didn't really look too interesting at first, huh?

Here's one last fun thing that occurred to me while I was thinking about this blog post earlier today:

It might be interesting to think about the Rhine monument and others like it alongside some uber-minimalist 1960s sculpture like Tony Smith's Die, one of many iterations of which is pictured above. There's a strong formal relationship, but the Rhine inscriptions really direct the viewer's relationship to the work.

Something to think about, anyway.

No comments:

Post a Comment